The ‘Cracked Actor’ documentary was first screened in the UK on 26 January 1975 - much to the displeasure of Mainman who wanted it to be shown the previous

month. The running time was 53 minutes and not the 90 minutes originally perceived. In addition, Alan Yentob’s planned title of ‘The Collector’ was dropped in favour

of, the more appropriate, ‘Cracked Actor’.

For the finalised programme, Yentob chose to focus on David so mainly used the interviews with him plus some commentary from fans. Clips of the performance at

the Los Angeles Universal Ampitheatre on 5 September 1974 were used plus some from the concert from Hammersmith Odeon 3 July 1973.

The documentary starts with a clip of the CBS News report featuring footage of David performing at one of the LA Universal Amphitheatre shows followed by an

interview with Wayne Satz.

AY: Since you’ve been in America you seem to have picked up on a lot of the idioms and

themes of American music and American culture. How’s that happened?

DB: There’s a fly floating around in my milk and he’s… he’s a foreign body in it, you see,

and he’s getting a lot of milk. That’s kind of how I felt - a foreign body and I couldn’t help

but soak it up, you know. I hated it when I first came here, I couldn’t see any of it.

AY: What made all of this important to you? I mean, with your background why were you

intrigued by all of this?

DB: Um… it was… I mean, it filled a vast expanse of my imagination. I was always pretty

imaginative and the imagination can dry up in wherever you’re living in England, often, if

there’s nothing to keep it going. It just supplied a need in me… America, became a myth-

land for me. I think every kid goes through it eventually but I just got onto it earlier.

DB: There’s an underlying unease here, definitely. You can feel it in every avenue and it’s

very calm. And it’s a kind of superficial calmness that they’ve developed to underplay the

fact that it’s… there’s a lot of high pressure here as it’s a very big entertainment industry

area. And you get this feeling of unease with everybody. The first time that it really came

home to me what a kind of strange fascination it has is the… we… I came in on the train…

on the earthquake, and the earthquake was actually taking place when the train came in.

And the hotel that we were in was… just tremored every few minutes. I mean, it was just a

revolting feeling. And ever since then I‘ve always been very aware of how dubious a

position it is to stay here for any length of time.

DB: This is the way I do cut ups. I don’t know if it’s like the way Brion Gysin does his or

Burroughs does his, I don’t know. But this is the way I do ’em. I’ve used this method only

on a couple of actual songs. What I’ve used it for, more than anything else, is igniting

anything that might be in my imagination and it… you can often come up with very

interesting attitudes to look into. I tried doing it with diaries and things and I was finding

out amazing things about me and what I’d done and where I was going. And a lot of the

things that I’d done, it seemed that it would predict things about the future or tell me a lot

about the past. It’s really quite an astonishing thing. I suppose it’s a very western tarot, I

don’t know.

DB: I never wanted to be a rock ‘n’ roll star. I never, honest guv, I wasn’t even there. But I

was, you see, I was there. That’s what happened. No… no it excited me just because it

was there, that was enough. I mean, personally I was playing saxophone and I was trying

to make up my mind whether I wanted to play rock ’n’ roll or jazz and as I wasn’t very

good at jazz and I could fake it pretty well on rock ‘n’ roll, so I played rock ‘n’ roll. And, I

found I enjoyed writing. The only thing I was ever really good at at school was

composition. Not grammatically, I was always terrible on grammar, but I could always

write better stories than anybody else.

DB: It was my initial fascination with mime and expressing things with facial movements

and body talk rather than articulating things. I mean, I’d one as much articulating as I’d

felt was necessary with the actual songs and if I was going to present them in more than

a single dimension, I mean, if I was going to present them visually then I wanted my body

or my muscles to play an active part in the performance. It’s funny that the same, very

similar masks to the Kabuki stick masks were then… were used with the English

Mummers Theatre. It’s very strange that they should come up with very similar designs

for faces. I don’t know what the link would have been but there must have been some

link.

DB: That is kind of from the Aladdin Sane album. Aladdin Sane was a schizophrenic.

That’s counted for lots of the… why there were so many costume changes, because he

had so many personalities that each, as far as I was concerned, each costume change

was a different facet of personality. This is, likewise, another Japanese costume. These

are all Japanese… most of this stuff is Japanese, most of my clothes are Japanese. I

have… I’ve always been fond of Kabuki style clothes. That’s another Aladdin Sane thing.

Aladdin Sane, I saw him as… I found light… lightning… a lightning bolt really represented

him.

DB: More than anything else I saw that a lot of my songs were very illustrative and

picturesque and I felt there were other ways of performing them onstage. I was never very

confident of my voice, you see, as a singer. So, I thought rather than just sing them,

which would probably bore the pants off everyone, I would … I'd like to kind of portray

the songs rather than just sing them. That's really how it started… wanting to portray the

material I was writing. I always found that my material… I felt that it was more three

dimensional. I wanted to give it dimension. I wanted to give it some other dimension other

than that of just being a song.

AY: You saw for a long period, or for certainly over the last couple of years, a lot of kids

sort of aping you almost or looking very like you so that they were… they would dress up

and put things on very similar to you.

DB: Yeah.

AY: How did you feel about that?

DB: Well, a lot of it came about starting off like that, but over the last year or so it’s

changing in as much that they’re finding out things maybe nothing to do with me but the

idea of finding another character within themselves. I mean, if I’ve been at all responsible

for people finding more characters in themselves than they originally thought they had

then I’m pleased because that’s something I feel very strongly about. That one isn’t

totally what one has been conditioned to think one is, that there are many facets of the

personality which a lot of us have trouble finding and some of us do find too quickly.

DB: Do you know that feeling you get in a car when somebody’s accelerating very fast

and you’re not driving? And you get that “Uhhh” thing in your chest when you’re being

forced backwards and you think “Uhhh” and you’re not sure whether you like it or not?

It’s that kind of feeling. That’s what success was like. The first thrust of being totally

unknown to being what seemed to be very quickly known. It was very frightening for me

and coping with it was something that I tried to do. And that’s what happened. That was

me coping. Some of those albums were me coping, taking it all very seriously I was.

AY: Wasn’t it a rather dangerous thing to do, to play the roles?

DB: Well I didn’t know. When you’re that mixed up and I’ve been mixed up man. I mean,

really it was… one doesn’t know. One half of me is putting a concept forward and the

other half is trying to sort out my own emotions. And a lot of my space creations are, in

fact, facets of me I have now since discovered. But I wouldn’t even admit that to myself at

the time. That I would put everything… just make everything a little kind of upfront

personification of how I felt about things. Ziggy will be something and it would relate to

me now, I find. And Major Tom in Space Oddity was something, Aladdin Sane. They were

all facets of me and I wasn’t really… I got lost at one point. I couldn’t decide whether I

was writing the characters or whether the characters were writing me. Or, whether we

were all one and the same.

AY: Would you say that Ziggy was a monster?

DB: Mmm. Oh, he certainly was. When I first wrote Ziggy… I mean, it was just an

experiment. It was an exercise for me and he really grew sort of out of proportion, I must

admit. Got much bigger than I thought Ziggy was going to be. I didn’t ever see Ziggy as

big. Ziggy just over-shadowed everything.

DB: Yes. I had a kind of… a kind of strange, psychosomatic death-wish thing, I think. But

that’s because I was so lost in Ziggy, I think again. It was all the schizophrenia.

AY: How much of Ziggy’s death have to do with his own personality or with the

circumstances in which he existed or with the…?

DB: Yeah, it was… really it was his own personality being unable to cope with the

circumstances he found himself in which is being an almighty prophet-like superstar

rocker who found he didn’t know what to do with it once he got it. Which is… it’s an

archetype really, it’s the definitive rock ‘n’ roll star. It often happens and I was just trying

to document it as such.

AY: It did look as if it was the ghost of Ziggy Stardust you were tying up?

DB: Yes, exactly. That’s what happened. It was trying to get rid of the damn character that

was kind of following me around. And… and hopefully… you see I’m very… I’m very

happy with Ziggy, I think he was a very successful character and I think I played him very

well. But I… I’m glad I’m me now… I’m glad I’m me now. My God I can trot ‘em out!

AY: So, David Bowie becomes a soul singer.

The US broadcast of this documentary contained slightly different footage to the UK. The main difference is that footage of David performing ‘John, I'm Only Dancing

(Again)’ was replaced with film of him backstage and in his dressing room:

The Young American

Cracked Actor Documentary

Alan Yentob discussing ‘Cracked Actor’

On 5 April 2013 Alan Yentob gave a lecture on the Cracked Actor documentary at the V&A Museum in London as part of the “Bowie Is” exhibition.

The evening began with a showing of the documentary. Following that, Geoffrey Marsh fom the V&A gave a brief introduction outlining the events of 1974 including

David’s arrival in the US, preparation for the forthcoming tour, the tour itself and the recordings at Sigma Sound Studios. He then turned to Alan Yentob:

WS: I just wonder if you get tired of being outrageous?

DB: I don’t think I’m outrageous at all.

WS: At all?

DB: No.

WS: Do you describe yourself as ordinary? What adjective would you use?

DB: Um…b… blah… ah… um… David Bowie.

WS: Ah-ha. Well, I’m reluctant to make the judgement about what category you fit into and I’m hoping to prove it.

DB: Good.

WS: Oh no, I wouldn’t be that pretentious but maybe you have a feeling yourself?

DB: No. I’m really very old fashioned. I like moving from one area of writing or performing to another… to keep me excited, to keep me interested, to

keep the people who come to see me or buy records interested and excited as well.

Wayne Satz concludes the report in the TV studio where he says, “If you didn’t understand that don’t feel badly because I certainly didn’t. David, I know you’re

watching tonight with the BBC film crew and it’s wonderful to have your old fashioned entertainment around, until the Beatles get back together, but it sure would be

nice to talk to somebody who’s not being evasive and discussing riddles.”

The documentary then continues with narration and interviews conducted by Yentob interspersed with live footage from Hammersmith Odeon 3 July 1973 and the

Los Angeles show. Some of this commentary is repeated below.

The Radio Times for the week it was first broadcast carried a 3 page spread…

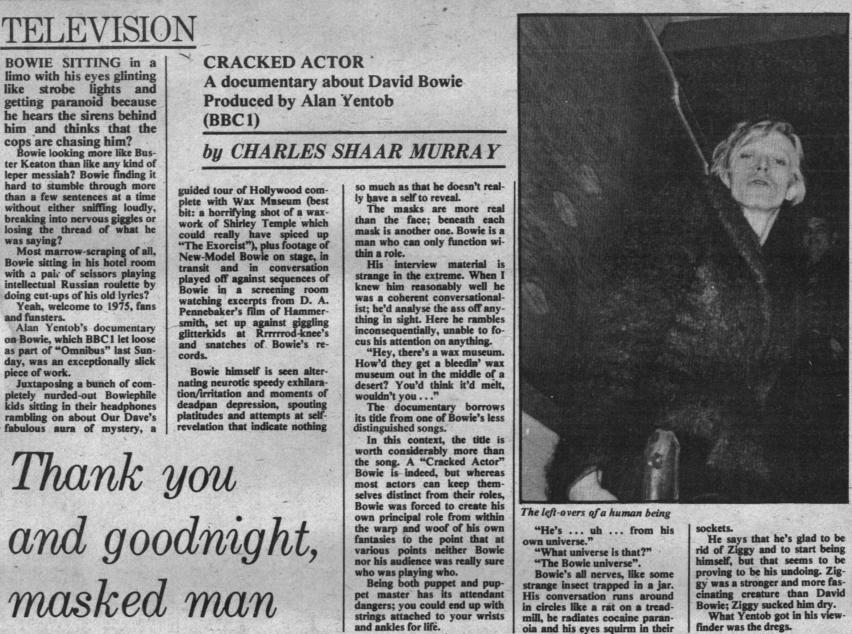

It was reviewed by Charles Shaar Murray in the following week’s New Musical Express…

GM: You were the same age as David Bowie when you made the documentary, had you met him before or seen any of his concerts? Had you been to

America before?

AY: I had seen him perform in London but I wasn’t at the farewell show. I had been to America and was infatuated with New York. Initially, I flew out to

New York to meet David and he said to come on board. I got him to agree to having the face mask made – a death mask or life mask, however you see

it. He trusted me enough to let me do that. I had planned to call it “The Collector” but then realised that he was a character who kept changing, that’s

what happened. I had a certain amount of money to spend and tracked down cameraman Mike Murphy – whose work I was aware of - in Malibu who

agreed to work with me. This film was a kind of early rock ‘n’ roll film. The thing about this was David’s generosity in allowing me to make the film. I

had to wait around a lot and, as you see in the documentary, most of the filming took place in the back of cars and in hotel rooms in the early hours.

David was frank and honest. It was a difficult time for him and he was very fragile but somehow he was prepared to share his concerns. That tour was

amazing because you could see these characters he had created who shortly he was going to dispense with.

GM: You had three months to edit it, What were your thoughts? Did you think that you had a fantastic scoop? You used other footage…

AY: We used footage from the Hammersmith Odeon concert including that incredible performance of “My Death”. For me it was about the narrative –

there were no other characters in it, no manager, no musicians, I decided to focus very much on David.

GM: Were you under pressure or worried about issues about drug use?

AY: I was under no pressure, there weren’t all those things that we have today. The drug use was implied, it wasn’t explicit. I wanted the narrative to

be about his own investment in those characters. What made it special at that time was David’s understanding of adolescence and his sympathy for

those kids stuck in a world they were trying to get out of and into another. He was creating music for a new generation yet he veered away from the

obvious. He was an experimenter.

GM: Given that MainMan/Defries instigated it, did they want to see it before it went out?

AY: No, today those things happen. I was fairly innocent myself at that time. Making films today is so much easier than it was back then, we used to

edit with a razor blade and it was a very laborious business. I found that the editor didn’t quite understand or have the sensibility to handle this film

but the (younger) assistant editor did.

GM: Cracked Actor looks more like a documentary about an actor rather than a rock star. Looking back, how did you see it, considering that

nowadays it would be considered a huge income generator?

AY: There was nothing promotional about this film at all, it was a character study. What made it special was that David was going through a

transformation as you watched it, a personal crisis in his life with an extraordinary display of creativity. It was how he dealt with it. It was really quite

simple, it was a series of encounters with David and his fans.

The floor was then opened up to take questions from the audience.

Audience: How did it feel to be in the back of the car? Did you feel it was going to be a great documentary? Did you feel you were speaking to David

or to another character?

AY: Well, I probably waited a very long time to get in that car! All I had in my mind was the type of film I wanted to make from the very beginning. I

knew I wanted to get the mask made. I knew the songs very well and how I wanted to use them. I knew that he wanted to finally dispose of these

characters and eventually celebrate them. I was always looking for the clues to this journey. Nic Roeg was looking for someone to cast in The Man

Who Fell To Earth and he saw the documentary and was convinced that David was the man for the role. He called me and asked for a copy of the tape

which he then used that to convince the producers to cast David.

Audience: There’s some great footage, especially ‘Right’, do you have the rest of it?

AY: I haven’t. There is nothing left in the BBC archive.

Audience: How much of the concert was filmed?

AY: We filmed most of it. It’s inexcusable that the BBC has lost it.

Audience: Does the BBC own the copyright.

AY: Yes.

Audience: It was a landmark film in David’s career which led onto many other things. How do you see your role in that?

AY: It was a truthful film, he let me into his dilemma and shared his aspirations. I am proud of the film and it does touch on what he is.

Audience: How much material does David have from that period?

AY: I suspect he has very little, especially considering the situation with Defries at the time.

Audience: How did you convince him to do the mask?

AY: He decided to go with it, to play the game.

Audience: Where did you find the kids?

AY: I just came across them.

Audience: What was the objective of making the film? What was in it for David?

AY: It was an ambitious, expensive tour and David knew that he wouldn’t revisit it. Therefore, it was ideal to document.